Beyond the normal horse race of it all, a lot of the conversation around the Tonys this year has focused on some pretty disappointing things—Patti LuPone’s mean-spirited comments to the New Yorker; frustration that Boop and Smash are not being allowed to perform, which is horrible for the business and also dumb—the opening number of Act II of Boop is exactly the kind of number that Tony Award show watchers long for.

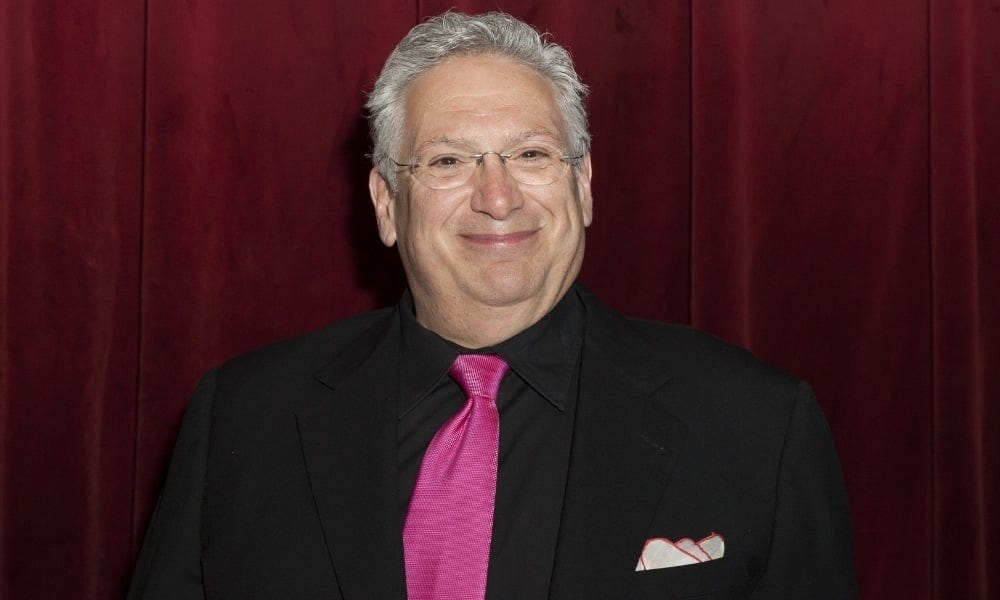

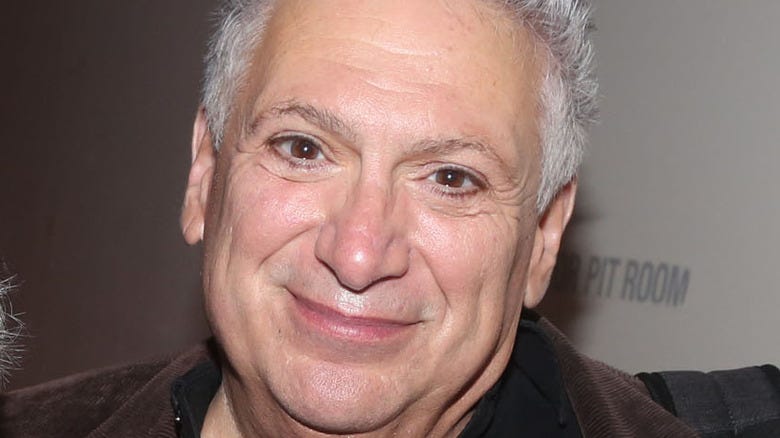

But the thing that has held my attention the most since it was announced is the fact that Harvey Fierstein will be receiving a special Lifetime Achievement Award at the Tonys tonight. A while ago I interviewed a number of the original Cagelles from Fierstein’s 1983 show La Cage aux Folles for a story for Dance Magazine. (A longer version of that piece was actually the inspiration for this Substack.) Prior to those conversations, I knew Fierstein mostly for his smart humor, his gravelly voice and his very funny turns in drag.

But in fact he’s spent most of his life breaking ground as an openly gay writer and performer, telling stories about being gay in a way unlike anyone else. Torch Song Trilogy, which launched him into the broader public’s consciousness and won multiple Tonys when it transferred to Broadway, was a revelation. It cast off that thunder blanket of shame and self-hatred in which shows like Boys in the Band had smothered queer experience, in favor of pathos, longing, and humor that felt true. Trilogy was a show that let gay men see and celebrate themselves, right down to the kinds of experiences and feelings they might have in a dark room, while also not putting straight audiences off.

This is the genius of Fierstein then and now: He finds a way of telling truth, without alienating those who might find it challenging. Where others would lead with pain or later rage, Fierstein always found room for connection and joy.

And that’s been true for his life as a public figure, as well. Case in point: In 1983, as La Cage was mounting its Tony campaign, Fierstein did an interview with Barbara Walters on 20/20. It’s pretty wild. Walters seems unsure at times how even to talk to a gay man. “What is like to be a homosexual?”, she asks around 4:45 below, as though he were some sort of alien from another planet. And you can see some of that surprise dance across Fierstein’s face as he tries to take that in. But his response is to engage with her, and to engage in a way that defuses her discomfort and even lifts her up with his acceptance of her.

It’s the very thing that made him perfect to bring on to write the book of La Cage. Today a show about a gay couple who run a drag club and have a son should not be at all shocking. But in 1983, just before the curtain went up on their first preview in Boston, La Cage book writer Fierstein, composer/lyricist Jerry Herman, and director Arthur Laurents feared the show was going to get them run out of town. It was a big swing.

Alongside Herman’s gorgeous melodies, part of the genius behind the show’s sucecess is Fierstein’s use of straight married life comic tropes, like the wife who feels overlooked by her husband, or the son who is easily embarrassed by his mom, to enable straight audiences to immediately feel comfortable in this world and with these characters. Some in the gay community (including Fierstein) wanted the show to go further in its queerness. But looking back what’s much more striking is that it got away with some of the raunchy jokes that Fierstein wrote, like the male statue on the end table whose penis is a cigarette lighter, as well as some of the affection that it showed. Gene Barry, who plays Georges, expressed anxiety that people would think he was gay for playing the role. But you can’t hear him sing “Song on the Sand” and not feel in your bones how much these two men love each other. (In his memoir Fierstein talks about watching an older straight couple take one another’s hand during that song at that Boston preview. He and the others knew then and there that they were going to be okay.

Within a few months of her interview with Fierstein, Walters interviewed Herman. She asks at the beginning, “Why doesn’t anyone know who you are, outside of the business?”

Herman responds by talking about being private and preferring his work to speak for itself. But underneath all that is a telling difference between Fierstein and most others on Broadway in the 80s: he was out, and they were not. At the opening night party for La Cage, the openly gay Village Voice reporter Arthur Bell famously asked Herman if the man who had just produced one of the most powerful anthems of gay life “I Am What I Am” could possibly not be gay himself. And Herman refused to take the bait. Just because he wrote about being gay didn’t mean he was. Except of course it did.

This is the other thing about Fierstein that is so important to recognize now. People look at Stonewall as this great moment when suddenly everyone was able to come out. But that’s not how it worked for a lot of people, including within the Broadway community.

Fierstein wrote about his life and world. He was going to be seen as gay whether he denied it or not. And somehow he had the courage to continue to be transparent even as he achieved great success and faced crowds that were uncomfortable with knowing this about him. There’s that moment in the interview he did with Joan Rivers on The Tonight Show where he mentions his lover. Moments later a couple in the crowd start tittering, in a way that suggests they don’t have any idea what to do with this information and so perhaps want to act like it was a joke. Rather than ignore it, Fierstein engages, in a characteristically welcoming, funny way. “I think a woman just realized I was gay,” he says. “These shoes didn’t tell you?”

He goes on into a very funny riff about having gone to an “all gay high school” and being taught there how to be gay, which absolutely wins the audience over.

During the interview, Rivers praises him for being so comfortable with himself. “You are so open about your homosexuality,” she says. “You’re so relaxed.” And that’s the thing with Harvey—in an era where being out “off-campus” was enormously fraught for most in the Broadway community, he somehow was able to convey a sense of ease and laughter about himself in public. In doing so, he helped others—straight and queer—feel about homosexuality exactly how he seemed to feel about it for himself: as something that was normal (and delightful). And he showed there were other ways forward for gay people in the Broadway community. You might want to keep your identity private within the community. Most still did for many years to come). But Harvey showed you didn’t have to. There was joy to be found in being open about yourself, even a sense of welcome. And he did all this in such an effortless way that the courage behind what he was doing, as well as the actual work of it, the keen sense of moving the community forward boldly is easy to miss.

In March, Fierstein announced on social media that his entire body of work has been banned from production at the Kennedy Center. Bravo to the American Theater Wing and Broadway League for responding by celebrating his achivements in this way and giving him a platform with which to speak. We who are queer are who we are today in part of because of the grace, the wisdom and the laughter with which he has led his life and told his stories (which include so many others that I should talk about and haven’t—most especially Casa Valentina).

Without many even knowing that he was doing it, Harvey Fierstein pushed open doors and enabled a greater space for LGBTQ people in this country and in life. And our lives and the theater are so much the better for it.

A wonderful article...thanks for this!

Delightfully written. Thank you.