THEATER WOW: LA CAGE'S CAGELLES SHARE THEIR STORIES, 40 YEARS LATER

Something About Sharing, Something About Always.

For some time now I’ve been obsessed with the making of the 1983 Tony-Award winning musical, La Cage Aux Folles. It was a groundbreaking work, the first mainstream musical to put at its center a gay married couple, who are treated not with derision but acceptance and dignity. And it was an enormous hit, which is shocking not only because it was so far ahead of its time in subject matter, but because it came to Broadway precisely as AIDS was first coming into the public consciousness.

The cast and crew of La Cage was very involved in fund raising efforts to help people who got sick. Their producers Barry Brown and Fritz Holt hosted the first major celebrity gala at the Metropolitan Opera. The show’s cast members did benefits constantly and all over the place. Some of those benefits continue to this day.

A number of the creatives involved in La Cage have either written books themselves—book writer Harvey Fierstein, composer/lyricist Jerry Herman, director Arthur Laurents—or in the case of executive producer Allan Carr, been the subject of them.

But there are so many other people that made La Cage so special. And among them are the amazing 10 men and 2 women who sang and danced in drag as the Cagelles.

I reached out to Dance Magazine last fall wondering if they’d be open to a sort of oral history of La Cage from the point of view of some of the Cagelles, as a way of celebrating their work on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the show. To my great happiness, they said yes, and three wonderful performers from the show, David Engel, Dennis Callahan, and Dan O’Grady, agreed to talk to me.

That article came out in mid-March. (Check it out!) But as I was writing it, I felt like I was perhaps not giving David, Dennis, and Dan the space they deserved. So below you’ll find a lot more. I hope at the very least it brings back a lot of happy memories for the guys, their fellow Cagelles and everyone in the La Cage family.

Special thanks to David Engel, who gave me virtually all of the photos you’ll see here. They are tremendous!

Anything good in the text comes from the guys and their generosity. Any errors are absolutely my own.

Something About Sharing, Something About Always

August of last year marked the 40th anniversary of the opening of the groundbreaking musical La Cage aux Folles on Broadway. As a way of celebrating the occasion, members of the original Cagelles—the 10 male and 2 female dancer/performers who formed the 12-person drag ensemble at the heart of the show—organized a series of events in conjunction with Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS annual fall Flea Market.

It was fitting that the group would decide to use that occasion of their reunion to raise money to help find a cure for HIV/AIDS. La Cage took Broadway by storm at almost exactly the same moment that news reports began to speak of a mysterious “gay plague.” And as that plague swept down upon Broadway companies, including their own, the Cagelles took it upon themselves to organize endless benefits, some of which continue to this day.

Most of the 10 gay men cast as Cagelles were little more than kids when they joined the show. These are some of their stories.

The Tiniest Threads

Dan O’Grady (Odette) : I started dancing professionally when I was in high school. In my junior year I was cast at the St. Louis Muny Opera, which is a local outdoor summer theater that hires local chorus and then brings in stars. That’s how I got my Equity card.

I graduated from high school the next year and went to SUNY-Purchase for a year. I got into their ballet program, and auditioned in New York all the time. That summer, I was cast in the touring company of Peter Pan. I did that and then got La Cage the following Spring.

David Engel (Hanna from Hamburg): In junior high I wanted to sing, I got into choir, and I had this soprano voice. I modeled my voice after Julie Andrews, and I was shamed for it by the choir director. “You’re a boy, you should sing like a man.” So I shut up completely. I got out of choir and wouldn’t go back.

But then in my junior year of high school someone dragged me into the theater department and I found out I was a natural. I went to college, but then immediately started auditioning for things. I did dinner theater near Disneyland, TV variety shows, the film Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. But I was completely untrained. I was just putting myself out there. That I even got Whorehouse was ridiculous.

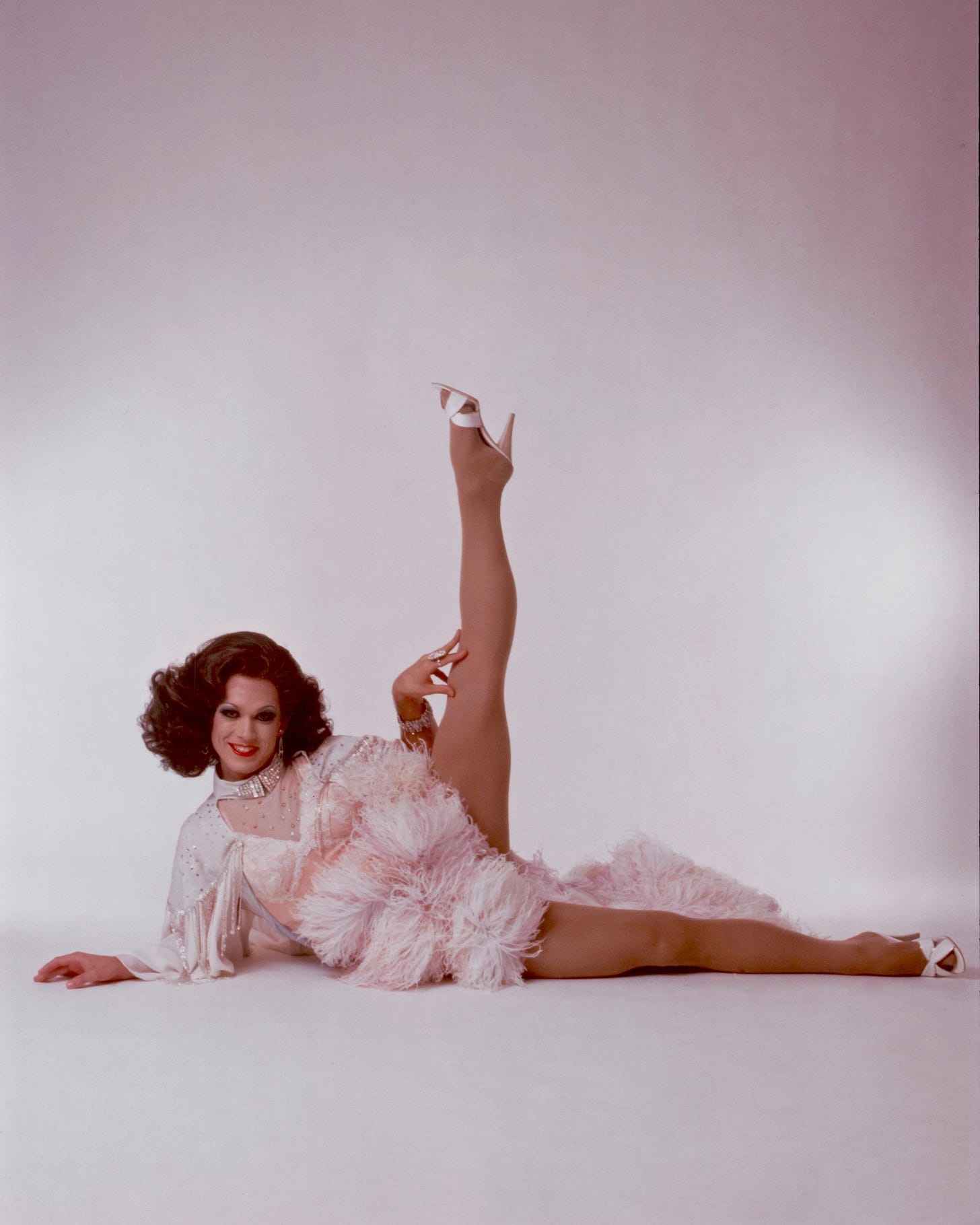

David Engel as Hanna.

Dennis Callahan (Monique): I grew up in Missouri. Boys didn’t dance there. So I didn’t really start dancing until I was 18. I went to the all-girls Stevens College in Columbia, Missouri. I had done a lot of sports, so I was sort of coordinated, but I had zero experience. But they took me on the basis of my body. They were desperate for men to be in their productions, basically, and I could imitate well.

It was an incredible education. The dance teachers there were really top notch. A week after I graduated I went into rehearsal at Muny Opera—Dan and I were sort of in different casts, but I was aware of him and also Leslie Stevens, who was the original Anne. And after that I had two years touring on Evita.

A Little Mascara

DC: I think there were between 800 and 1000 at the original open call. We had the advantage that Scott Salmon, who was the choreographer, was not a New York person. He had worked on shows in New York, but he had primarily been in Los Angeles, and he didn’t know anybody. So it was really like a clean slate as far as what he was seeing at these auditions. And Scott was a doll—he was a sweet, sweet man. I remember from the auditions, when you would go in and sing for him, he had this smile on his face the whole time. He wasn’t judging you, he was just happy you were there.

DE: I was only being seen for Jean-Michel. I’m the only person that they brought out from L.A. I went through at last three more auditions in New York. They kept calling me back, and then they said we need to see you dance and we actually need to see you in drag, because at the end of the show they wanted Jean-Michel in drag. They said, Can you come to the final dance call? Everybody else had learned all this choreography. I learned it on the spot.

I actually made a skirt, too, and I had this blouse that was belted. They said, we need to see your legs, and I was able to take the skirt off. The blouse was long enough. It was so cute.

DO: It got down to maybe 25 of us at the end, and they said come to the Lund-Fontanne on whatever day it was, we’re going to put you in makeup and costumes. And I had never done any drag at all, it had never really interested me. But I had these friends, Bobby Grayson and Guy Stroman—Guy was one of the original Forever Plaid guys, and Bobby is a hair and make-up artist, he does all the celebrities. And Bobby offered to do my hair and make-up for the final call back. So I decided I was going to show up and drag.

I stayed at their apartment that night, and we got up really early and they did my hair and make-up, and put nails on me. It was hilarious, really, really funny. When I got to the cab, the cab driver got out, opened the door for me, called me Ma’am. Then I went into the Lund-Fontanne, and [executive producer] Fritz Holt was there, [director] Arthur Laurents, [executive producer] Barry Brown. And they didn’t know who I was when I walked in. No one else arrived in drag.

Dan O’Grady as Odette.

DC: They told us to bring dresses and heels, then they sat us down and put us in full drag. All of a sudden we were watching ourselves become our mothers. And they paid a lot of attention in that final callback to how our jaws were shaped, and how much space we had between our eyes and your eyebrows. There were no really square-jawed people, and none of us had really furrowed, heavy brows. That was a big factor, how were these 12 guys going to appear, would they be able to pass as women?

From 10 in the morning to 4 or 5 in the afternoon, we did all of the dancing like that, and we had to sing our original audition numbers. My audition song was “I Don’t Remember Christmas,” which is a really masculine song, but then I had to get up and sing it in drag.

DE: [At the end] basically it was like the end of A Chorus Line. We were all lined up across the stage. I remember I was fully stage left—I kind of put myself there, because I knew they weren’t looking at me for this, they were still looking at me for Jean-Michel.

DC: At the end of this long day, we were 12 and 12 across the stage. I remember looking down across the aisle and thinking those are the people who are going to get hired, that’s the side that I want to be on, and I wasn’t.

Then at the very last minute, they said, Dennis would you switch with someone on the other side. And the two of us had to walk by each other. It was intense. And I switched to stage right, then they said, Everybody on stage left, thank you very much.

DE: And then they said to everyone else, “Rehearsals start on this date, Congratulations. And everybody’s jumping up and down screaming, and I’m like What’s happening? What’s going on?

And Arthur comes down to where I was, and he says, I know we brought you here for Jean-Michel, but we actually need somebody who’s strong in the chorus who can also cover Jean-Michel. And we would like to give you a little featured part.

I was so disappointed. *laughs*

It was my first Broadway show, my first Broadway audition, and I get it and I’m like *sigh* Okay.

I wouldn’t have it had any other way. I’m so happy where I landed. It was great to be a Cagelle.

DC: After the others left, they had the 12 of us gather around the piano and sing “There’s no Business like Show Business” in real short clipped piano voices. We sang the whole first chorus like that. (Composer) Jerry Herman said, This is the style of La Cage’s opening song, “We are What We Are.”

It was such a cool moment to be around the piano with Jerry and (music director) Don Pippin, all of us in drag.

Dennis Callahan as Monique.

Not a Place We Have to Hide

DE: The very first day of rehearsal, Arthur Laurents said, we are not doing this apologetically. We are proudly playing these roles.

Arthur Laurents in rehearsals for La Cage.

DO: He gave us all storylines. We weren’t just playing drag queens, everyone had a story. Some were more developed than others, but we all had a bit of one. Arthur really instilled in us that we were important to the story, and that it was important that we comported ourselves onstage with dignity. It made it less for me about drag and more about integrity.

DC: Though I don’t think any of us had any experience doing drag, I don’t think any Cagelle would say it was hard. The atmosphere in the room was so supportive and nurturing that none of us felt any fear of being judged. There was never anything negative, it was all positive.

DO: I remember Arthur working with George Hearn (Albin), a straight man, on “I Am What I Am.” I was one of the Cagelles on stage every night during that song. And the amount of pride and dignity that Arthur conveyed not just to George but all of us was very powerful. It moves me even just to think of it now. I felt so accepted in that world.

DC: The Cagelles were given the last bow. When does that ever happen? That was something. We all lined up, our backs were to the audience. One after another we took off our coats and our wigs and threw them in this cart as it walked by, and then our arms went straight up into the air and we turned around. It was always such a rush, a total transformation. We each took a humble bow as ourselves, the ten men and two women. The sound of the audience was unbelievable.

Count All the Loves that Have Loved You

DO: Scott Salmon was absolutely one of the loveliest human beings I ever met. Beyond a kind person, he was very generous. He worked with our limits and our strengths. There are a lot of choreographers who will capitalize on shame and humiliation to motivate a dancer. That was not at all how Scott worked. He really believed that performers need to be built up. Arthur was the same way. [Book writer] Harvey [Fierstein] and Jerry were also part of our rehearsal process, and they were great.

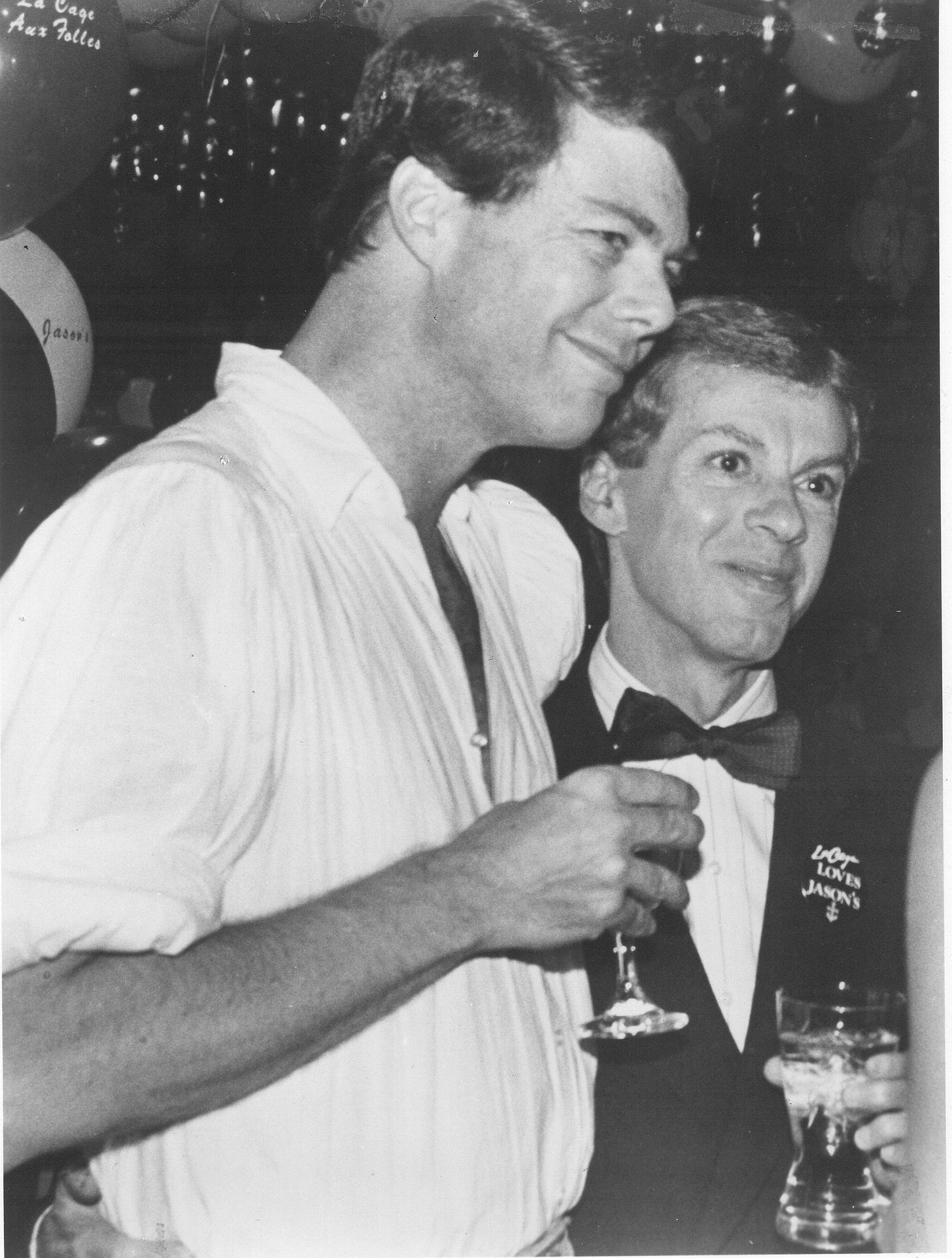

DE: Executive producer and stage manager Fritz Holt was just adored by all of us. Everybody loved Fritz. He was our stage manager for a while and he was executive producer, and he was, I don’t know, Santa Claus. He was the heart and soul of that show.

At the table read, usually everybody goes around and introduces themselves. But for ours instead of that Fritz went around and put his hands on each person’s shoulder and talked about them—not just the creatives; he went to every single person and stood by them and spoke about them. All of us. He was telling people about our careers and what we had done prior to that, just introducing us. That’s how we met him. He was just a joyous human being. He made everyone feel important.

Fritz Holt and Arthur Laurents.

DC: George Hearn and Gene Barry (Georges) were two straight men who from the beginning embraced what they were doing. Gene had a little trouble getting into it; it’s a bit of a thankless role, you know? It’s all about Zaza, all about George Hearn. And I think he had done a Broadway show before, but after having been on a TV set and playing Bat Masterson for most of his life, he was so unfamiliar. It was a little overwhelming.

But I must say he rose to the occasion, he really did. In “Song in the Sand” and “Look Over There” he has the most romantic moment and the most telling theatrical moment in the show. I think he realized that as time went on.

I always remember their last moment, when they’re walking upstage shoulder to shoulder, and George would take Gene’s hand and wrap his arm around his waist as the lights faded. It was such a beautiful moment. It was just right.

George Hearn and Gene Barry.

DO: Linda Haberman (Bitelle) was really inspirational to me. I just couldn’t believe that I was in the same line as an original cast member of Dancin’. I was not at the same level, mind you, I was a child. But it felt good. And I learned a lot from her about professionalism, working hard, dancing full out every single time.

Linda Haberman as Bitelle.

Also Mark Waldrop (Tabarro), Jennifer Smith (Colette), who was one of the townsfolk and then took over as Anne when Leslie Stevens left. Jennifer was and continues to be one of the hardest working people in the world. She knows what she does well and she moved toward her challenges rather than avoiding them. I thought I had to sort of veil areas of technique where I wasn’t as strong. She was like, No, you need to embrace that shit. You need to move towards it. I learned a lot from her.

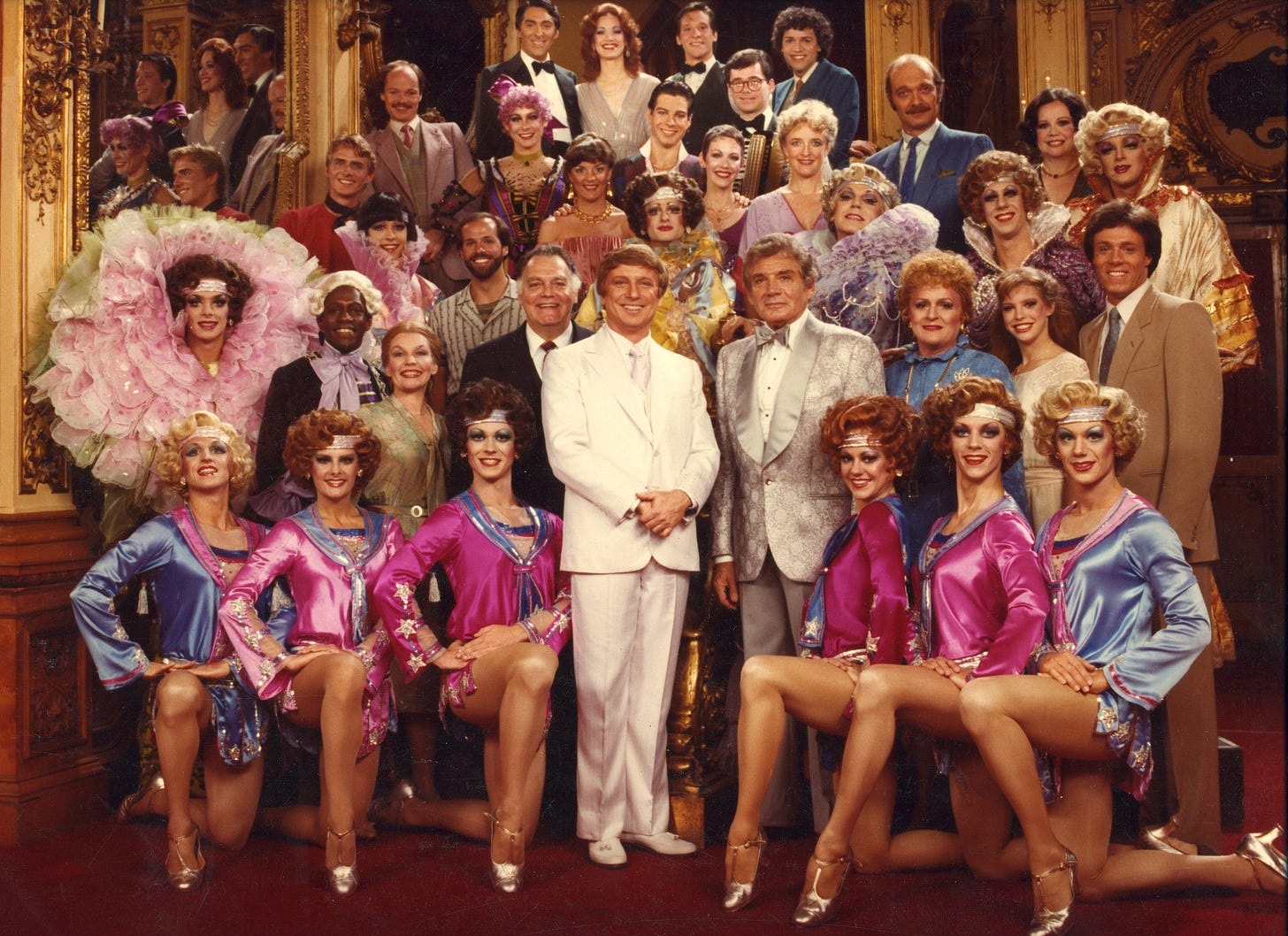

DE: One of the things they did right off the bat was, once we got the great reviews in Boston, they brought the twelve of us into the ladies lounge of the Colonial Theater, this glorious rococo gold-leafed room, and they said, We are giving you guys a name. We’re calling you “the Cagelles.” At the time I thought, What a dumb name. I really did, I thought, You can’t think of something cleverer than “Cag-elles?” *laughs*

Then they said, We would like to double your salary. And they did. They wanted to keep us together.

DC: When the show closed in 1987, out of an original cast of 35 people I would guess that 23 or 25 were still there. Which tells you, we were treated like gold. Every six months we received an extension and we got a raise in salary. From the first day, we just had a feeling of family that was so special.

Sometimes Sweet and Sometimes Bitter

DO: We liked to entertain ourselves. We would put on little shows or do little things just to amuse ourselves. Madonna was getting big right then, and she had some kind of video contest for one of her songs, I think it was “True Blue.” David Engel had all or most of us do this little video that he submitted.

DE: We were such a fricking hit. We were sitting fat and happy in a run, and we knew we would be there for a while. So we would entertain each other all the time. We had a whole warm up area in the basement of the Palace, and at intermission, we’d dress up, we’d be ridiculous. We just kept creating and playing. We were always making shows. I was part of this trio called the Miss Haps, we were beauty pageant contestants, two guys and a girl singing three part harmony, but we put the girl on the bottom part. We wore these bathing suits with paunches and tall beehives. We had really funny names.

The Miss Haps.

We would do it for our own parties, and then we started doing it at clubs.

It was the best of times. And it was the worst of times.

DO: I first started hearing about the “gay cancer” when we were in Boston. Nobody knew what it was. It was the summer of ‘83; the New York Times hadn’t even put the words AIDS in print. You kind of heard a little bit about it here and there, but not much. It was kind of more a San Francisco thing.

DE: So little was known. I remember Gene Barry was concerned about breathing the same air with all these gay people. He wouldn’t put himself in a small room with us. He was vocal about that. AIDS was so new. So little was known.

I myself, if I went to a gay bar, I would hold my breath. I don’t ever remember feeling in danger within the cast. You felt safe. But I felt like I was in danger outside the group. You just didn’t know.

It was everywhere, and if you tested positive, it was a death sentence, definitely. You knew it was, and you could go quick. I remember visiting David Cahn (Chantal) in the hospital. He had had a stroke or seizure or something, he couldn’t talk. It was not even that long after he left the show. And then he died right after that, and you wished it for him.

DO: I think David [Cahn] was the first of us Cagelles who got sick and left, and then John Dolf (Nicole). David and I were good friends in Boston, I actually understudied him as the opera singing Cagelle. And I sat next to John Dolf for 2 ½ years in our dressing room.

DC: I don’t remember any conversation between the rest of us about the boys being sick. It just wasn’t talked about. It’s odd to think about now; now it would all be out there. But I think it was sort of a feeling of if they wanted to talk about it they would, and they’re not, so neither should we. And maybe there was also a fear.

When we lost Larry Lynd (Monique) in the Los Angeles company, I remember them assembling us before the show and saying We’ve lost Larry. All of us knew who he was, because we always had parties where you would meet the other casts, and we saw their last run through.

It loomed large.

DO: We felt the loss from the inside, and I think that’s what sort of led us to start thinking about the Easter Bonnet competition. We were just kind of doing it for ourselves, dressing up and being ridiculous. And then we decided to do these Easter bonnets. Howard Crabtree and the other costume folks did all these silly bonnets, and we had folks donate. In the beginning it was just the cast, the crew, and the orchestra.

DE: We did the Easter Bonnet pageant in the basement, we did a Queen of Hearts pageant for Valentine’s Day, both just among ourselves, and raised money for the Gay Men’s Health Crisis. Then the next year we decided to bring the Easter Bonnet pageant up onto the stage and invited other casts to come— A Chorus Line, Cats, there were a few companies. I remember when they flipped over the cards at the end we had raised seventeen thousand dollars. I was sobbing, sobbing.

The Easter Bonnet competition has continued ever since the Cagelles started it. Here’s a photo from last year’s celebration.

DC: We were involved in a lot of things. Early on, Fritz and Barry Brown organized an AIDS gala at the Met, all kinds of prominent stars were there. It was one of the early things like that, and it was fantastic.

One night after the show three of us, David Scala (Phaedra), Sam Singhaus (Clo-Clo) and myself went to Marie’s Crisis and other piano bars in the Village. It was a benefit for something. We did “Hey Big Spender,” I think, a little bit of “We Are What We Are,” a couple other numbers. And we sang live and had these little lilac dresses on that we bought down in Chinatown.

DO: I think we needed a sense of agency. Because there was no hope. There really wasn’t. AZT wasn’t even a thing at that point. Our friends were dying, and we couldn’t do anything about it. But we could dress up and act silly and ask people for money.

DC: Teddy Azar was our make-up and wig designer. He had done a lot of work on Broadway, he had done 42nd Street. He was really talented, instrumental in the whole look of the show make-up and wig wise. And he was one of the first in the company to come down with AIDS.

He was at St. Vincent’s, and David, Sam and I got some nurse drag with these giant hypodermic needles and resuscitation devices, just ridiculous stuff, and we went down there.

It was the first time any of us had been on that ward. It was pretty shocking. But to walk into Teddy’s room and see his face lighten up…

People who worked there came up to us and said, Could you please come bring some of this joy into some of the other rooms? And we went in and out of these rooms, these three big old drag queens in nurse drag, and it was joyous. The whole thing was joyous.

Fritz Holt and Teddy Azar.

DE: I had plenty of hard losses, but the hardest was Fritz. They pulled us all together to let us know that Fritz was in the hospital, and then my goodness, a week later we got the call, Come in to the theater. I remember it being one of those days like 9/11 where it was pristinely beautiful. I was cursing the weather. I was like, How dare it be sunny and beautiful out.

We got to the theater. We all gathered downstairs, and they told us. And we just cried and cried. Then we left to go to our dressing rooms to get ready. And I remember none of us spoke. We just did our make-up. And you’d hear sniffling and crying, and then we’d all start crying. You couldn’t keep the make-up on. We were all just sobbing through it.

Without speaking we all went up onto the stage. They dedicated the performance to Fritz, and we silently got in place, because the curtain rises to us. And one by one we turn around in the opening number and we all start singing “We Are What We Are.” But then one by one voices are dropping out. We just couldn’t sing. We were all crying. The cast members in the wings on both sides were singing for us, trying to keep it going.

It’s so hard for me to talk about it still. I remember telling this story for Ghost Lights [an upcoming documentary] and I couldn’t get through it. I put my arms out to the side, the way that we did on stage, and I was going ‘We are what we are,’ trying to show them how we were singing, and I was crying.

That whole show we didn’t talk. We did all we could just to get through it.

It was a bad time.

Hey World, We Are What We Are

DC: We had a very shallow orchestra pit at the Palace, which meant you had a real connection with the audience when you were on stage. We would come out in the opening number and our backs would be to the audience. And when we would turn around one by one, you could feel physically this sort of crossed arm, furrowed brow feeling from the audience. Because AIDS had just started. They were probably wondering if maybe we’re too close, we’re going to get it.

By the end of the show those same faces were leaning into the stage, wide-eyed. I left every night thinking Wow, I think I was part of something that changed what people think about homosexuals.

DE: Arthur and Jerry were out gay men, but they weren’t public figures like Harvey was. You see Harvey on The Tonight Show when he says “I’ve got a lover at home” and the audience is like, snickering. Because it’s shocking. Except for like, a Quentin Crisp, nobody else was being out. But Harvey was.

This is the clip of him on that Tonight Show. Harvey is funny, at home with himself, and completely fearless.

Boy, I was stealth in public. In the theater world I was out and it was fine, but otherwise I knew how to blend in and pass for straight. You could be gay in the theater world, but publicly people just weren’t out.

I remember getting asked to host something at some gay bar in Jersey. And I apologized there, I said to them, I’m not really gay, I just play one on stage, or something like that. This is at a gay bar. Later I was like, What was I thinking? I remember I had to get comfortable with being out publicly pretty quickly.

DC: I came from a family that was so supportive. My mom and dad raised 5 kids, and I was the youngest, and from the beginning they saw something in me. They would take me to the Muny Opera, to the Starlight in Kansas City, and nurtured that in me.

But at the same time I didn’t ever feel like I needed to tell them I was gay. I thought the words and the situation would hurt them. And they knew.

When they saw the show, that was my way of being able to tell them and show them that I was going to be okay.

DE: I came out to my mom when I was 18, and she really struggled with it. She couldn’t understand what she had done wrong. It was La Cage that turned her around. She said that it let her know that you can have love and family being gay. She became the proudest P-Flag waving mother ever. She would tell everybody, “I wish all my kids were gay.” *laughs*

She became a mother to all of my gay friends that had parents that disowned them. They adored her, and she loved all of them.

Arthur Laurents, Jerry Herman, and Harvey Fierstein.

DO: La Cage changed my life. I got to work with Harvey Fierstein and Jerry Herman and Arthur Laurents and Fritz Holt and Barry Brown and Don Pippin, and George Hearn and Gene Barry and Merle Louise, with whom I later did the original company of Kiss of the Spider Woman. The work ethic, the creativity, and the artistry was like nothing I had ever been exposed to. At the time I didn’t think of myself as a serious artist, I thought of myself as you know, a chorus boy. And that was fine, I was a kid. But later I came to appreciate what they instilled in me, the work ethic, the importance of taking my work seriously.

I can’t say I was always a serious person in La Cage. I was young and I was dumb and I did a lot of dumb things that people did in the ‘80s. But I learned from them, and people were incredibly kind and patient.

DC: At the 40-year reunion that we just had in Times Square, we sang “The Best of Times.” We were swaying back and forth. And there were two older gentleman sitting next to each other in the audience, and they were bawling. And I thought God, this show affected more people than we will ever know.

It’s so special to have been a part of something like that. It was the reason that I never really wanted to pursue any show after that. I thought, What am I going to go do, Cats? Nothing’s going to compare to that feeling of making a difference.

The cast of La Cage Aux Folles.

I cannot thank David Engel, Dennis Callahan, and Dan O’Grady enough for their willingness to talk to me about La Cage, and at great length, and to the others from the show that have also agreed to speak with me since. I feel incredibly humbled at the stories they’ve shared and the trust they all have shown me. I hope they feel like this piece gives some voice to their experiences.

Georges sings in “Look Over There”—

How often is someone concerned

With the tiniest thread of your life?

Concerned with whatever you feel

And whatever you touch?

In the midst of both their own success and a devastating pandemic that most people turned away from, the Cagelles and the cast and crew of La Cage stayed concerned with the threads of so many other people’s lives, and continue to do so to this day.

To them, with gratitude for their humor, their generosity, and their lives.