"It Wasn't A Broadway Show...Until It Was"

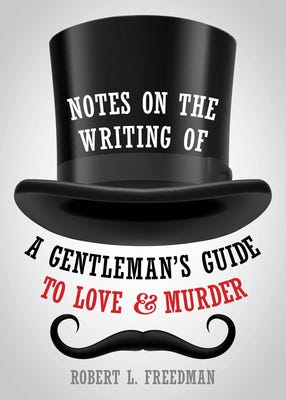

A Gentleman's Guide to Love and Murder writer Robert L. Freedman talks his Tony-winning musical and the "memoir and manual" he's written about it.

Robert L. Freedman is the Tony Award-winning book writer and co-lyricist of A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder, as well as the Emmy-nominated writer of TV miniseries Life with Judy Garland: Me and My Shadows, and many other things.

In February, Freedman came to BroadwayCon and shared insights from his book Notes on the Writing of A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder, a marvelous look at how he and composer Steven Lutvak developed their hilarious, anarchic musical about a young man in Edwardian England who discovers he is actually the distant relative to a wealthy family of aristocrats, and sets out to murder everyone between him and the inheritance. Adapted from a 1907 novel which had already been adapted into the beloved British film Kind Hearts and Coronets, Gentleman’s Guide did not seem like an obvious Broadway vehicle to many who saw or heard about it during the many years of its development, nor to Freedman and Lutvak either. Freedman’s story of how exactly that happened, and the collaboration between he and Lutvak, director Darko Tresnjak, and actor Jefferson Mays, who plays the 8 members of the D’Ysquith [DIES-quith] family whom lead character Monty Navarro must murder, is a valuable glimpse into the creative process of musical theater.

I spoke to Freedman by phone. Our conversation is edited and condensed for clarity.

What made you want to write Notes on the Writing…?

I got approached by Applause Books. Steven Sater, who wrote the lyrics for Spring Awakening, had written a book [about lyric writing]—same size, same length—and Applause wanted to do another one.

I wanted it to be two things: A story about Gentleman’s Guide, the writing of it, the making of it; and a structural book about what book writing is in terms of a musical, and how musicals are written. Things that book writers have had to deal with. Because I think book writing is kind of misunderstood.

So it’s a little manual, I guess, and a little memoir.

Using your own experiences on Gentleman’s Guide was a great way into the topic of book writing. It put meat on the bone.

In fact, I found that it had insights into book writing that I had not seen before. Like the idea that choosing a setting that is not exactly the normal world can be really valuable in helping your audience ease into your story.

I just feel that sometimes when shows are completely contemporary, they’re a little harder to like. I mean, sometimes I love them, it’s not that don’t I love shows that are contemporary, I do. But it’s something that’s just personal to me.

Also your idea that your choice of names in a story—whether you’re adapting material as in Gentleman’s Guide or writing something original to you—gives you a sense of ownership of the material and helps establish a tone.

It’s a completely fun part of Gentleman’s Guide. I’m tickled by it to this day even. And it really matters. It does.

And it’s going to be individual [to your] life experience. I remember I was writing something way back when, collaborating on a movie script, with another writer, and I suggested naming a character Vicki. And she said Vicki can’t be the name of the person. Why? Because she knew a Vicki that was a horrible person.

You talk about the importance of picking material you feel a connection with. What was it about the Gentleman source material that spoke to you?

Bryce Pinkham, center, as poor-kid-wanting-to-rise Monty Navarro, and Lisa O’Hare and Lauren Worsham as Sibella Hallward and Phoebe D’Ysquith, the women he loves.

I would say that there were two elements that I first connected with. One was the style, the tone. The novel was written by a man who was part of Oscar Wilde’s circle, and it’s witty.

It’s also a really searing indictment of the aristocracy, the hierarchical level of the way people lived in England at the time (and still, probably), the stark division between the haves and the have-nots. It was an examination of that.

Then the second thing was, I loved the lead character, because he was underestimated at every turn. His charm allowed him to ingratiate himself with people, but he started off in a bad way. He was raised in poverty but he had access to people we would call upper middle class today; he was in love with somebody who wasn’t ever going to marry him because he wasn’t rich and influential enough, important enough; and his mother had been discarded by her wealthy family and scrubbed floors, did people’s laundry for a living. So I just thought he was a compelling character.

I wasn’t looking necessarily to write anything about murders or anything, but Steve had seen this movie Kind Hearts and Coronets which is also based on the novel, and we both just thought it was so droll, so funny. People who have seen Gentleman’s Guide but knew nothing about the movie have sometimes told me that they didn’t think it was as good. Well, it’s a classic. What Casablanca is here, that’s what Kind Hearts is in England. It’s considered one of their top 10 British films of all time. But it was not widely known here.

I love hearing about your process of discovery, how the same source material that created such highbrow wittiness became this enormously inventive, silly piece of musical theater.

Well, we wrote a musical comedy, and that is not what the movie is. It’s definitely a comedy, but it’s not a laugh-out-loud funny movie at all. I love it, but it’s its own thing.

That’s the whole thing about adapting something, you have to find yourself in it and make it your own. You can’t just take a movie or a book or something and put it onstage. People have tried. *laughs*

And they usually fail that way. Because you have to turn it into another entity—not because you want to change what is there, but it just evolves as you work on it.

Can you remember distinct a-ha moments where you and Steve realized your version was actually going to be this anarchic, crazy story.

I think it was gradual. I don’t think it was like, Okay we’re going to make this sillier. It just happened over time.

And it was enhanced by meeting [director] Darko Tresnjak and having him become involved, which I think was around 2009. (We opened in 2013.) He would think of ways to stage some of the things we wrote.

It’s Jefferson Mays also. Darko suggested Jefferson because he’d worked with him, and Jefferson really threw himself into the characters when we did readings, Which we did many, readings and presentations, all kinds of stuff. Jefferson understood the milieu so well and the characters so well. He’s a huge Anglophile, much more than Steven and I. He really knew his stuff.

Jefferson Mays (right), as Asquinth D’Ysquinth, Jr., one of 8 D’Ysquinths he plays in Gentleman’s Guide. (Also pictured, Heather Ayers as Miss Evangeline Barley and Ken Barnett as Monty Navarro, in the Hartford production.)

He’s also just really brave. He literally threw himself into it, I mean he did pratfalls at readings. He was enormously influential; I felt like I had another collaborator, it wasn’t just an actor playing a role. Like, I think when the priest is describing the church and its architecture, he said to me, Give me some more of that. He had fun playing with that. So I would dig up some stuff and give it to him, and he just knew how to do it. That just made it richer and funnier.

Or he did an ad lib one time, the dialogue was, Monty shows him a picture of his late mother, and D’Ysquith Senior says, “Oh she looks very much like the women in the family, and some of the men.” Jefferson added “some of the men.” I wasn’t too proud to not use that. When you have an actor of his caliber, they’re going to bring something to the show.

Another useful insight from the book: When you’re writing a musical you have to think, What can we afford? Can we really have 20 characters? What do we really need? And in the case of Gentleman, your small cast and budget really enabled you to do things in fun, creative ways. Like when the minister is up in the church tower, to signify how windy it is Jefferson throws his scarf around like it’s blowing and then messes up his hair. It’s hilarious and also so clearly tells me what this show is.

Incredible. He did the thing with his hair one day and we all just rolled over, it was so funny.

Sometimes you think Ah if I had more money I could do more, but then it turns out maybe no, if you have less money you can do more.

Yeah. We made a virtue of the fact that we had a small cast and a simple set.

I’ll also give a lot of credit to Darko and Alexander Dodge, the set designer, and of course Linda Cho who designed the costumes. Darko understood, because he’d done it so many times and done it so many times with Alexander, how to get the most with the least.

Everything came together in the right way, is all I can say. I think it made it even more special than it might have been.

In the book you talk about how important it is that the creative team are all on the same page, and the disasters that can happen if you're not all telling the same story.

I wonder, would you have advice for people on how to test for that, how to know if you’re all rowing in the same direction? Because it seems like it can all go off the rails without people necessarily knowing it.

Yeah, and perhaps by the time you realize it [it’s too late].

Gentleman started with Steve and me. We had been friends for 20 years before we ever started writing it. We met at the program at NYU. [Freedman and Lutvak were classmates at the Tisch School’s graduate musical theater program.]

Robert L. Freedman with his Gentleman’s Guide writing partner and friend Steven Lutvak.

So we shared a certain outlook and sense of humor. We weren’t the same person, we were very different people actually, but we shared certain things in common. And I think when he came to me with the movie of Kind Hearts, which he himself had been dreaming of doing for years, and he asked me to take a look at it, I think he must have instinctively understood I would get it.

Which I did. And I saw that it could be a musical. I’ve heard people say, Who would look at that movie and think it could be a musical? Well Steve and I both did, enthusiastically. So right there we were on the same page.

That didn’t happen by accident: We really knew each other, we knew each other’s humor. I think that helped.

And Darko understood it from the very beginning, too. From the first meeting we had with him, he understood it. It was very, very clear. We were never at cross-purposes, and so everything the designers did and the actors did just elevated it.

What was it about Darko in that first meeting that showed he got it?

Cast members Jefferson Mays and Bryce Pinkham with Darko Tresnjak (center) on Opening Night.

He was just so delighted by the kind of subversive quality of it. He used to say, I’m not called Darko for nothing. He liked that it was a very dark story told in a very funny way. He got what it was. And this was his first Broadway show, so he had probably already directed 50, 60, 70, plays and a few musicals all over the country. He was a very well-respected regional theater director. And he’d done a lot of Shakespeare, so he knew the vocabulary.

We never had a question of who the characters were. I don’t remember him ever saying, I don’t understand this character. I don’t think so. I don’t remember any conversation like that.

He had a lot of wonderful staging ideas, which I talk about in the book.

You do. And reading them really captures that process of discovery.

And listen, there were things he suggested that I pushed back on, and things he pushed back on that I wanted to do. So we learned how to navigate that. He got some of what he wanted that I was skeptical about, and I got some of what I wanted that he was skeptical about, and it all worked out really well.

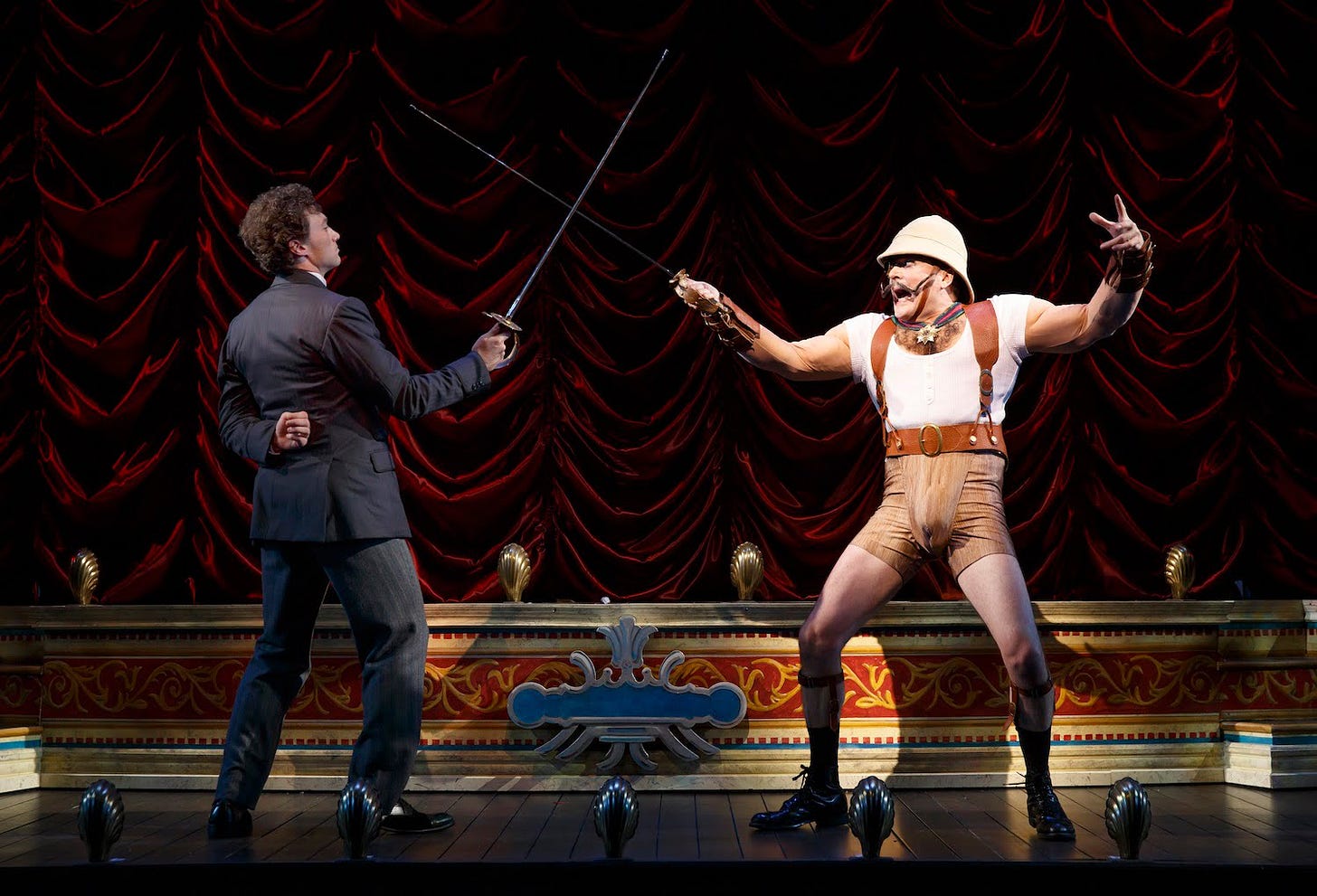

Monty (Pinkham) duels Lord Bartholomew D’Ysquith (Mays).

Darko’s inclination was to go for the gruesome, and I was hesitant. I didn’t want it to be a bloody musical. So with the weightlifter, Lord Bartholomew, the barbell was just supposed to break his neck, but Darko wanted it to sever his head. And I said, Darko, I think that goes too far. And he said, You know what, let me have the prop people rig it up, and I’ll just show it to you.

So we sat there, and we’re talking no costumes, no sets, no lights, nothing. And all of a sudden the severed head popped out in such a funny way. Literally it was like CRUNCH and the head just rolled to the side. It wasn’t gruesome, it was hilarious. I couldn’t remember when I’d laughed so hard. And I said great, let’s do it.

The way that idea started was with a different character who was doing Hedda Gabler, she shoots herself offstage. Darko wanted a severed head to roll onto the stage after that. I said, Darko, when you shoot yourself, there’s no severed head. And he had another idea for her, so it worked out great.

But then we come to the bodybuilder and he wants to do the severed head again. Again I was skeptical, but it turned out.

I think one of the genius aspects to the death scenes is that you allow them to have multiple beats. The priest falls and dies in this wildly visual and funny way, and then just lies there. Thinking it’s over, we focus on Monty’s shock. But then out of nowhere this enormous pool of blood stars to emanate from the priest’s body. And that becomes the pattern—each death gets these unexpected extra beats.

I knew there was going to be blood, but it wasn’t really until I saw it done that I realized what it was. And I don’t remember this exactly, but I bet I thought, Oh I wonder if the blood’s too much. But from the very first audience, they went nuts over it.

Absolutely.

It’s one of the biggest laughs in the show, if not the biggest maybe.

You just don’t see it coming.

Yeah. And I love that.

The other thing was, I was very much against vulgarity. I wanted to keep it very Edwardian in that sense. So I was like the vulgarity police. But there are still a few things in there that skirted very closely.

Was this your first time doing lyrics as well as book?

Not. It was my first time doing lyrics for a Broadway show, although when we wrote it—honestly, of course one dreams of going to Broadway, but we would have been thrilled to have a production, period, anywhere. It was a long time coming. But it was a thrill.

I remember being surprised by songs like “Inside Out,” this incredibly sweet and tender song set in the midst of an insane bee attack. To me, it’s like a magic trick to have created such a beautiful moment in the midst of such a preposterous situation.

Lauren Worsham, nominated for a Tony for her work as Phoebe D’Ysquith, sings “Inside Out”.

That was our intention. We had an idea the kind of song that this character would sing, kind of an art song if you will, a highly proper song, beautiful melody and everything, and somewhat poetic and virtuous, all of those things, and then juxtapose it. The song gets silly as the action got silly with Henry being chased by bees. But it was always written with the idea that it would end with him being killed by the bees.

Were there things that helped you in terms of writing lyrics? You’re doing Edwardian language, so you have the challenge of keeping the audience following lyrics that don’t sound familiar and sometimes move really fast, yet you never lost us.

When we got to play in real theaters, Broadway especially, I was very concerned about the sound. I didn’t want people to miss the lyrics. Without a great sound designer like we had, Dan Schreier, I don’t know if people would have heard every word. It was really important to me.

But I had people say the had to see it two or three times before they got everything. But that’s true of almost any show in a way.

Absolutely.

I think Steve and I just wallowed and reveled in the language and being able to do it and to do it amusingly. We used to crack each other up a lot. We would really try to find the wording and the rhymes and everything, we worked really hard on it, but it was fun, because it was funny.

I don’t know what the magic is, except part of it is hard work. And then I guess we had an affinity or I guess you could say a talent for that kind of stuff. Whenever one of us thought a line or a word or whatever, the music wasn’t quite right yet, it could be better, the other would say, Great, let’s keep working on it and see if we can make it better. We were hard on ourselves.

What’s funny is, when we started off we didn’t have a producer, we didn’t have a director, we didn’t have a theater, we didn’t have a commission. *laughs*

We had nothing. We just wrote it for our own enjoyment. Of course we wrote it to be seen by people eventually, I’m not saying that. But we weren’t hired to do it, we weren’t encouraged to do it, we just did it. Because that was what we wanted to do with our lives, essentially. So we just did it.

I guess that’s my biggest piece of advice to anybody. Write what you want to write. I mean, no one would have hired us to write this, because not one would have thought it would make any money.

That's so true.

Actually at some of the readings that we had, the readings used to land really, really well, but people would say Well, it’s really good, but it’s not a Broadway show. That's the thing we heard a few times. “It’s not a Broadway show.” Until it was. *laughs*

Someone had to believe in it. Darko had to believe in it, and [producer] Joey Parnes had to believe in it, and the New York Times had to believe in it.

The cast performs at the 2014 Tonys, where the show won Best Musical, Book, Direction, and Costumes.

It wasn’t off-Broadway first, was it?

No what happened was, after Darko got involved, Darko was the Associate Artistic Director at the Old Globe in San Diego. And while we were doing this together, he got hired to be the artistic director of Hartford Stage in Connecticut. And he decided Well, he loved this show and he’d been working on it with us anyway, so he’s going to put it in his first season.

Wow.

It was going to open the season, but he said, You know what, I want a production of Hedda Gabler right before it. So when the Hedda Gabler joke comes…*laughs*

Are you kidding?

No I am not kidding. He said, In New York, I’m not worried. In Hartford, Connecticut…? It was a great production of Hedda Gabler.

Somebody got the New York Times to come. Which was terrifying, actually, but they loved it. And then we already had planned a co-production with the Old Globe. So after Hartford we went to the Old Globe in San Diego, with a couple of months in between. And once it got to the Old Globe, Broadway producers started being serious, so after the Old Globe we had our Broadway producer. Then it took a few months to get a theater and whatever. It closed in April of 2013 in San Diego and it opened in November of 2013 in New York, which actually I think is kind of a short time. But it was not off-Broadway.

You know how there have been shows that were on Broadway and now they’re doing them off Broadway?

Yes.

Darko said the other day, he thinks Gentleman’s Guide would be a great off-Broadway show, it could run forever.

I absolutely agree.

The conventional wisdom is that you can’t make money off-Broadway. But look at Little Shop. Of course it was a really-known entity by the time this revival happened, they’d had a movie, it was already a classic show. But still…But I think Jersey Boys went off-Broadway and Avenue Q. The Play that Goes Wrong.

There’s a show I saw off-Broadway a couple seasons ago, Dead Outlaw, now coming to Broadway. It has a similar anarchic creativity to Gentleman’s Guide about it.

My wife saw it. She loved it.

Like Gentleman’s Guide, it’s a show where the premise sounds unproduceable.

I’ve heard the premise and I still can’t get it. But when something is well done, it doesn’t really matter. Listen—this is hard to believe now, but when I first heard the premise of Evita, I thought, Really? It’s a musical about the mistress of a dictator from Argentina? Whoever heard of her? I mean, Really? Now Evita is part of the canon. But I thought, What a strange idea for a musical.

Jesus Christ Superstar—what an audacious, unlikely idea for a musical. But we’re used to it now because we live in a world where it’s considered a classic.

Thanks to Robert L. Freedman for a wonderful conversation. Notes on the Writing of A Gentleman’s Guide… is available everywhere. And the musical A Gentleman’s Guide… is available for licensing via Music Theatre International.

Enjoyed this very much...thanks for the MTI shoutout as well.