Glenn Drewes is the Happiest Guy in Show Biz

A profile of trumpeter and New York jazz icon Glenn Drewes.

This article, which will be published in the spring in the International Trumpet Guild Journal, is published in advance here by special permission of the International Trumpet Guild. Big thanks to ITG Journal editor Peter Wood for allowing me to do so, and also to Glenn Drewes and his many friends for all their help and patience.

The week that Broadway reopened in 2021, I went to see the long-standing revival of Chicago. Somehow the idea of seeing a show that had been around for so long—25 years at the time—felt like the most appropriate way to honor the many, many New York City performers who had struggled through the 18 months that theater was shuttered.

It had been many years since I first saw the show, which made it an absolute delight to watch, each new scene bringing a fresh sense of surprise. And the show’s most striking moment for me was also its most unexpected: During the entr’acte at the start of Act II, a trumpet player stood and delivered the hottest damn take on “Mr. Cellophane” I’ve ever heard. It was so steamy that the actors on stage actually stood and cheered him on. I’d never seen anything like it.

Two years later, I went back to Chicago and it happened all over again—at the start of Act 2, the same trumpet player stood to do this solo. He was an older-looking guy with a shock of thick white hair, and when he blew the cast went wild. It was clearly a mutual thing, too; when he was done he pointed at various cast members, beaming.

Who was this guy, I wondered, and what was going on here?

It turns out, his name is Glenn Drewes, and he’s a New York City legend.

A Long Island Renaissance

I first met Glenn at an Irish bar between shows one Sunday. It was the opening weekend for Vanderpump Rules star Ariana Madix as Roxie, and the audience for the matinee had gone crazy for it. “I used to not like Saturday matinees,” Drewes told me as he sipped a bit of the brown stuff, “but I’m starting to. Today was electric.”

Sitting up close with him, the first thing you notice about Drewes is that he’s got a kind of a glow to him. No matter what we’re talking about, or how dark the bar gets as the sun goes down, there’s a joy that radiates out of Glenn Drewes.

Originally from Brooklyn, Drewes moved to West Babylon, Long Island as a toddler and spent his childhood there. That one decision on the part of his parents might have been the most pivotal of his life. His high school music department was run by a guy who “saw the future coming down the road.” He hired working musicians to teach the kids at night, and a number of those children would go on to become renowned professional musicians, including Drewes and his brother Billy, who plays sax; trumpet player Vince DiMartino; Sal Spicola, who played sax alongside Chuck Berry; and Dennis Wilson, who played trombone with Count Basie. “There was one after another,” Drewes says, “who all came from that little school in a 10-to-12-year period, because this guy had vision.”

Growing up there was music in the Drewes household, too. “Our dad didn’t play piano for a living,” Glenn’s brother Billy explains, “but he could entertain with all of the old songs. He was great, a big influence on both of us.”

Drewes had been playing piano himself for four years when that great music teacher came around to show kids different instruments they could try. Glenn still remembers the moment: “He took his trumpet out and played, and I said, ‘That’s it. That’s what I want to do.’”

Even before he finished high school, Drewes was doing professional gigs. “I was working Friday, Saturday, Sunday, these little bar gigs,” he recalls. “My dad used to drive me because I didn’t have a license.”

It was eye-opening right from the start. One night, he recalls, he walked in for a show and the leader of the band told him the manager wanted to see him. “Am I getting fired?” Drewes wondered. “No, we’re playing an act tonight,” the band leader explained. “And you’re the only one that knows music here.”

Unsure what exactly that meant, Drewes went to the manager’s office. Inside, he recalls, “There’s a beautiful woman sitting on a chair, naked.” At age 16, he was speechless, to say the least. “I would like to have a picture of my face,” he tells me, shaking his head.

“You must be the trumpet player,” the woman told him. “My name is Cassandra. Have you ever played a strip show before?” Learning he hadn’t, Cassandra gave him a lesson that Glenn says he has kept with him to this day.

“Here’s the deal,” she says. “When the lights go down, you start to play. And the more clothes come off, the hotter you get.”

“She taught me the business in like 30 seconds,” Drewes says now of how that one direction helped me understand playing the trumpet.

He’s not kidding, either. Glenn Drewes knows how to turn up the heat. In 1999, he was part of the orchestra for Fosse, the Tony Award-winning review of Bob Fosse’s work. During the last number of the show, there’s an incredible two-minute sequence in which Drewes blows alone center stage as a female dance performs in front of him. With just a few notes he creates a whole world full of fire and mystery through which she struts, kicks and spins. It’s an absolute showstopping moment, visually and musically.

Glenn and dancer Lainie Sakakura doing the number.

That night at the club, Drewes left Cassandra wondering how he could bring what she wanted without a plunger. And so he improvised. He literally went to the bar’s bathroom, grabbed the plunger, washed it off, and played the show with it.

“I play the plunger really great now,” he kids.

Crazy and Great

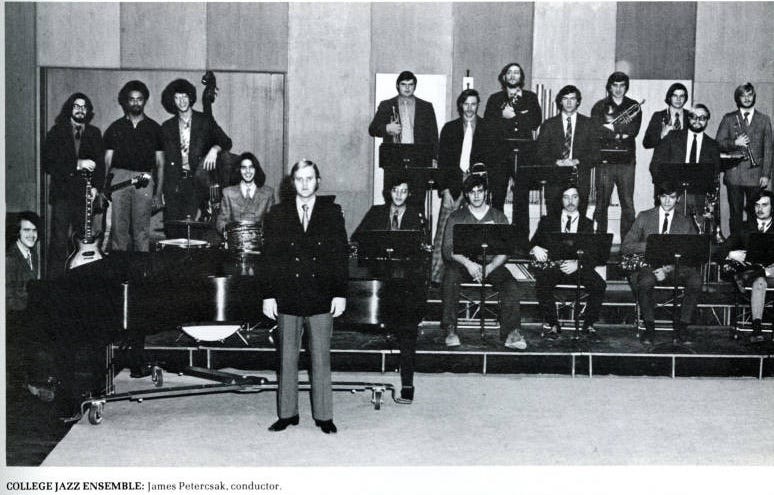

The College Jazz Ensemble at SUNY-Potsdam, 1971. You can see Glenn in the back row, smiling as he holds his trumpet with his arms crossed.

When Drewes finished high school he did a degree at SUNY-Potsdam, and spent the entire time playing music. “I joined a group out of Syracuse which was a drummer, a girl singer and two of my buddies,” he said. “The drinking age was 18, and there were four universities within ten miles. Every other store front had a bar with live music. We had about 60 arrangements. We played dances, we played jazz gigs, we played rock and roll.”

“I like to say that I got my bachelor’s degree from the school, my master’s from playing with [saxophonist] Gary Keller, who was at school with me, and my PhD from playing with that group.”

After graduation, Drewes got the chance to tour with jazz legends—Lionel Hampton, Woody Herman. He loved life on road. “You’re in hotels, you’re playing music every night, you’re out with a bunch of people.” But after a bunch of years, he also realized if he didn’t get off the road soon, he might never. So he and a pal from the band bought a loft in New York on 23rd Street and started hustling to find work locally. His longtime friend saxophonist Bruce Bonvissuto remembers the era: “We were doing club dates, Greek and Polka type of stuff, Jewish clubs, all sorts of stuff. We were doing whatever we could get our hands on.”

Having that kind of adaptability and energy has always been part of the nature of playing music in New York. “Everybody that I know that’s been successful in New York (except for the symphony players, who just do that), have played in everything from Latin bands to wedding bands to major recording sessions and movie dates,” Bonvissuto says. “I was Julliard-trained, I [initially] made my living playing principal in freelance orchestras, I’ve done a lot of recording work, I’ve done Broadway, I’ve done club dates, I do jazz gigs. I don’t think there’s any place in the world that’s as open as New York is to good musicians just doing all sorts of stuff.”

Drewes recalls how recording jingles was of the great money makers when he first settled into the city. “Every 13 weeks you got a [residual] check” for any aired jingle he played on. “And say Budweiser used the music but changed either the film or the wording of the commercial. Say they changed it six times. You got six checks even 13 weeks.”

“I got in on the tail end, but the guys who did it heavily bought houses,” he says, laughing. “It was crazy and it was great.”

The Big Ears MVP

As we talk, Drewes repeatedly attributes the work he’s gotten to good fortune. “It’s all luck,” he says.

Pretty much none of his colleagues share that point of view on his success. “Glenn is kind of like the Derek Jeter of the music business,” says Bonvissuto, who hired Drewes to join the orchestra for Chicago. “He’s got great energy, he’s extraordinarily versatile. He makes everybody around him better.”

Trombonist and composer Mark Miller, who has played with Drewes for over a decade at Birdland Big Band, agrees. When you’re putting together a big band set, those early solos are so important. “You want to put one of your best people first. If they light the room on fire, it helps us,” he explains. “It gets the juices flowing. And Drewes has been that for many years.”

I saw that for myself at a recent Birdland visit. After an opening number that sets the mood, Birdland leader David DeJesus called for Terry Gibbs’ “Big Bad Bob.” It’s a big swinging number that features first a trombone solo, then Drewes on trumpet. And as soon as Glenn starts playing, pretty then playful then brassy, it’s like the whole room opens up, and we’re all together in the moment, musicians and audience, enjoying the experience. One of the saxophonists starts clapping along. Soon we all are.

Someone on YouTube posted parts of a Birdland show, which includes Drewes on “Big Bad Bob” (at 8:00). The first song of the set also features Brandon Lee, and the last, “Your Smile” (29:33), was written by and features Mark Miller. You can see a characteristic moment of Drewes’ positivity at the end.

At times Drewes’ speed can be dazzling, the notes whirling out of him. But where some jazz soloists can specialize in flights of fancy that are by turns breathtaking or personal, exploratory, Drewes as a performer seems much more interested in being a great host, delivering the best party in town. “It’s not some introspective moment that he’s having with himself,” Miller says. “His sound is big, he’s trying to give everyone a good time. I love that.”

Bonvissuto agrees. “A lot of modern players play what we call ‘outside,’ which is a little hard for a non-musician to get close to or listen to. Glenn plays more traditionally—he’s a very lyrical player. His jazz solos are creative and inventive. He’s got real command over the instrument. It’s enjoyable to listen to.”

When I ask Birdland trumpeter Brandon Lee how he’d describe Drewes’ style, the first word that leaps to his mind is “happy”: “Emotionally, when you hear him play, the way he plays and improvises has a sort of happy quality, this sort of brilliance.” Listening to Drewes, he says, “I imagine it’s like when people would say they’d heard Louis Armstrong live, how different it was from hearing recordings, just how big and loud and very trumpet-y.”

Trumpeter Earl Gardner has been playing with Drewes in various bands and orchestras for over 40 years at this point. He first worked with Drewes in the Mel Lewis Big Band at the Village Vanguard. One night the band unexpectedly found itself a trumpet down between sets; Lewis suggested Gardner call Drewes, whose apartment was nearby.

Drewes came, did the set, and wowed Gardner. “I call him my MVP,” Gardner explains. “He can cover any book on the band. Officially he was a third trumpet—you get to play solos here and there on certain things, but basically you’re playing parts.” But if the second trumpet had to take off, Drewes could step in on the spot and play that book, and the same for the jazz trumpet—“He’s a really good jazz player,” Gardner notes. He could even cover for Gardner in the lead seat, never an easy seat to fill. “The lead trumpet book is an important thing. You’re the voice of the band.”

“Drewes was a luxury,” Gardner said of playing with him at the Vanguard.

Gardner also praised Drewes’ ability to play as part of a section. “It’s not just about playing your part, you have to be listening to what’s around you and fitting in. He can fit in any situation, and he knows all kinds of styles.” Bonvissuto agrees: “He’s got big ears. You put him in a situation that may be not what he’s used to doing, but he just keeps his ears open and adjusts to the style, and the way people around him are playing, and he makes it work.”

“He can do so many things,” says his brother Billy. “He can do Sesame Street, he can play parts, he can do Broadway shows, he can solo behind a singer, he can do a jazz gig. He’s one of those people that’s not pigeonholed.”

The Long Island Music Hall of Fame celebrates internationally famous Long Islanders—Billy Joel, Cyndi Lauper, Steven Van Zandt, George Gershwin. In 2018, they instituted a new award, “The Hired Gun Award,” for “musical ninjas”—as Hall of Fame co-founder Jim Faith put it—who could be thrown into any situation. The first winners: Billy Joel’s long-time guitarist and Glenn Drewes.

Drewes receiving his award in 2018.

Charlie Hustle

Drewes and Earl Gardner (to his right) with the Mel Lewis Big Band.

If you ask Drewes himself, the real key to his success has been his “just say yes, just be positive” work ethic. “There’s always an emergency and they call you because they’ve heard your name and they need somebody,” he explains. “And you have that one shot. Don’t go in there like an egomaniac. Just go in nice and do your job.”

It was being ready to say yes that got him working with Gardner. After he’d subbed that one set, Gardner invited him back, but warned him, this was probably not going to be a regular gig. “I told him, ‘Look, I’m going to keep the chair open, because I want to try some different people. In the back of my mind I’m thinking, ‘This guy is working all the time, he’s not going to want to do this.’”

But then the next week when Drewes came back, he sounded great again, and “we were having a great time,” Gardner remembers. “At the end of the gig I said, ‘Can you make next week?’ He said, ”Yeah, sure.’”

“That went on for 10 years,” Gardner reveals, laughing. “I’m serious. He was never officially hired. We had the ten-year anniversary of him being in the band, and I looked at him and I said, ‘Drewes, I guess we’re officially hiring you.’”

In 1988, Mel Lewis took the orchestra to Imatra, Finland. Their last song “Don’t Get Sassy” (which begins at 27:00), features a solo from Drewes (at about 30:00). His brother Billy Drewes is also featured.

“I call him the gig machine,” says Gardner. “There’s not a gig that he’ll turn down.” He recalls a gig Drewes took recently that paid basically nothing and involved a lot of driving. “I asked, ‘Why are doing it? You know you could have said no, you don’t owe anybody. What’s wrong with you?’”

It’s the same with doing Birdland each Friday right before his curtain at Chicago. “He’s blowing his brains out on the other thing, then he comes and does the show, which is a demanding show. I asked, ‘Why are you killing yourself?’“

But the answer is obvious: “He loves it. He just wants to play.”

In 1981, just saying yes would also lead Drewes to one of the most important moments of his life. “Lena Horne was coming to Broadway, and they were going to do it with a rhythm section and two horns,” he explains. “Then they found out that in the theater, they had to use a band.” A friend playing in A Chorus Line got asked to do it, but he didn’t want to leave his show. So Drewes got a phone call at 3 in the morning, asking him if he was free.

Drewes ended up playing for Horne for a year and a half, and also recorded an album with her years later after getting another last-minute phone call from a friend. “Is that my pal Drewsie?”, she said when she saw him. “I give her a hug and she goes, ‘Come on,’ pulls out a little flask and says, ‘We gotta have one together.’”

“Here I am with Lena Horne, doing that,” he says, marveling at it. “You can’t make this stuff up.”

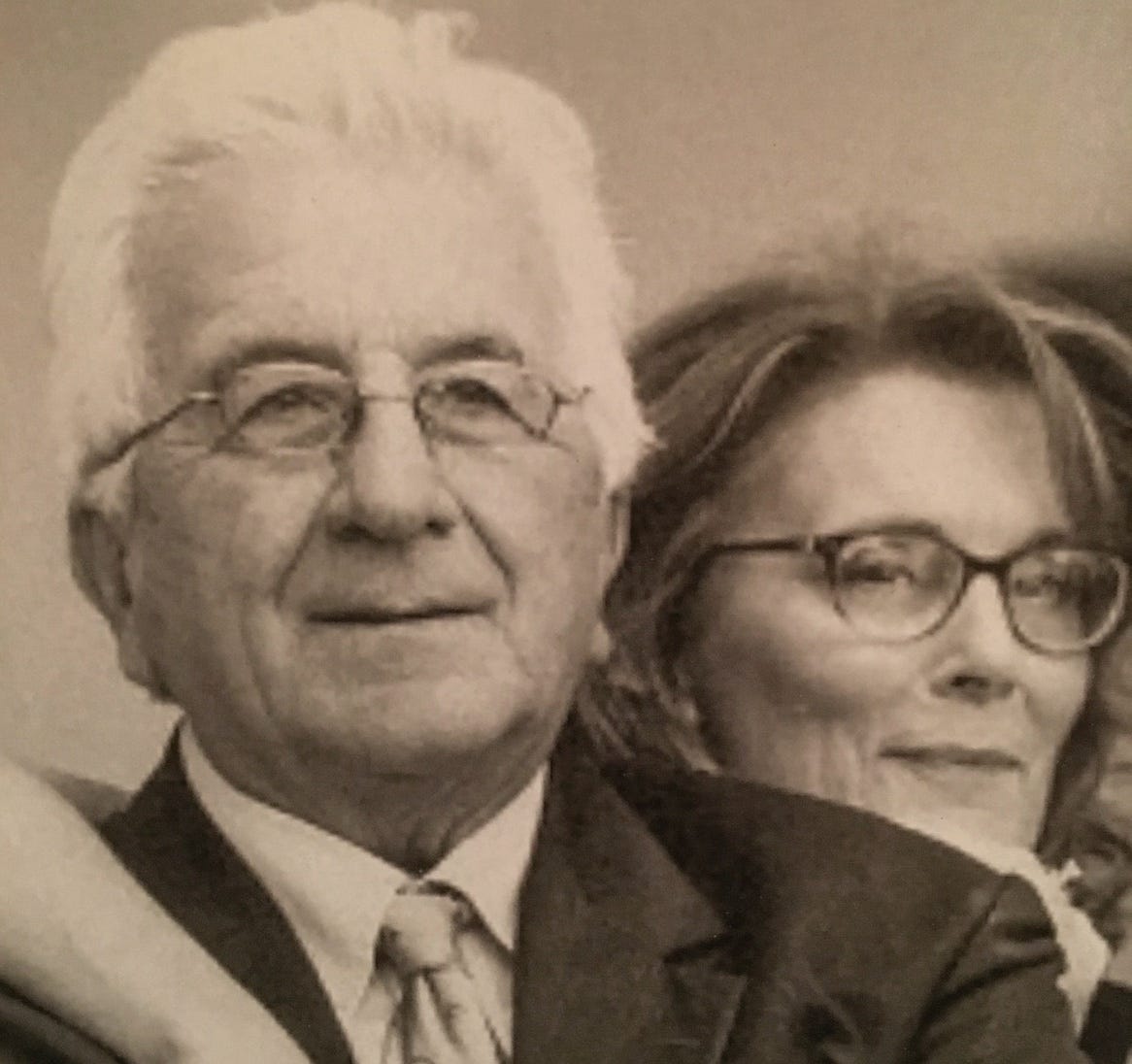

While he was playing in the orchestra on her show, a friend from high school called, asking if he could get tickets for a friend who was a nurse. Drewes was waiting with the tickets when she arrived, assuming she’d be bringing her boyfriend or husband. Instead she was with a girlfriend. “We start chatting, and I say, ‘You want to have a drink after the show?’” That night, she went home and told her mother, “I just met the man I’m going to marry.” And eventually, she did. “It took her 8 years to get me,” he kids. “But we’re still happily married.”

Glenn and wife Wendy.

DREWWWWEEES

Drewes stands in the back row center in this photo of the Birdland Big Band. Tromobonist Mark Miller, who has also composed a lot of music for the band, stands on the right end.

When I first interviewed Glenn, I had not seen him in play with the Birdland Big Band, which he has been doing every Friday night for almost 20 years at this point.

The first time I went, Drewes was actually away on vacation. But he might as well have been there for as much as he got mentioned by band leader DeJesus. In fact DeJesus had picked out a number of the songs specifically because they were Drewes’ favorites, as a sort of valentine for him. And every time Drewes got mentioned, the band and staff and regulars would call out “Dreeewwes.”

I’ve been back many times since when Glenn is present. The delight that everyone involved with Birdland seems to take in Drewes is always the same. “He’s always cheerful, always positive,” Miller says. “He’s a magnet—he just draws people to him.”

His brother Billy says it’s the same everywhere. “He’s well liked. He has a positive attitude for every situation, and nothing is ever too low. He’ll do all kinds of jobs, and he’s committed. People can count on him.”

Lee notes how much Drewes’ attitude has impacted both the trumpet section at Birdland Big Band and the band. “Other sections can be a little standoffish or competitive,” he explains, which can make it tough, especially when you’re subbing in and already dealing with the anxiety of that. “People haven’t heard you play before, and you kind of have to prove that you can exist in different sections.”

“The moment I feel like I have to try to prove something, immediately I’m in my head, and that means I’m not playing exactly to my potential.”

Meanwhile at Birdland with Drewes and fellow trumpeters John Walsh and Raul Agraz, Lee says, “it’s just a very welcoming, very happy, very loving section. We have a true friendship with each other. And I would say Glenn definitely is the spearhead of the energy that we feel.”

You can see that rapport when the four of them are standing on stage together. They’re always in the back kidding around. And when one of them has a solo, the others stop and turn to face the player, smiling and showing their support. “The whole time I’m playing the solo, they’re just kind of egging me on,” Lee says. “It’s like, ‘YEAH.’”

One night I got to watch Drewes and Lee sharing a solo on the Rob McConnell and the Boss Brass song “My Man Bill.” The number flies like a racehorse charging out of the gate. Drewes and Lee pass the solo back and forth between them, their tempo and shadings perfectly in sync in a dazzling, strutting blur of sound and color.

That warmth that people get from Glenn Drewes extends beyond the bandstand, too. When Lee moved back to New York after five years in North Carolina teaching full time, Drewes reached out to offer him work subbing in on Chicago, and the other Birdland trumpeters followed suit. “A lot of times, people hold those chairs pretty close to their vests,” Lee explains, “usually because they already have a long list of subs, and they can’t bring anybody in. But he’s always encouraged me. I always feel like he and they have my back, the whole time.” As a result of having subbed in on Tina for John Walsh, Lee got on the radar of the show’s contractor. He has since been had chairs of his own on two different Broadway shows.

Andrew Grossbard, who co-leads and directs the Long Island Sound Big Band, first met Drewes as a high school student on Long Island. The great jazz composer and saxophonist George Bouchard ran a program at Nassau Community College which brought in professional musicians, including Drewes. “He was so humble, so forthcoming of information for anybody that wanted to talk,” Grossbard says of Drewes.

Over the years he’d ask Drewes about everything from getting into the music scene or more music theory kinds of questions—“What are you doing on this chord, are you thinking more melody?,” he explains. “The way he improvises, he very much tells a story. He can say more with a couple notes than most can say with a lot more.” And Drewes was game for all of it. “It’s not often that you get somebody of that stature to be forthcoming,” Grossbard notes.” A lot of times they’ll be like, ‘You want to learn this? Study with me. I charge X. Or buy my book.”

“He’s just a tremendous person and musician.”

“I’ve probably played more notes with him over the years than anyone in the business,” Bonvissuto tells me. “It’s one of the highlights of our careers, these friendships that we’ve been able to develop.”

And Gardner, who now plays with them both on Chicago, agrees. “It’s a joy to play with him,” says Gardner. He talks about the “telepathy” they have seemed to share from their very early days playing together. “When I first started doing Chicago, I would close my eyes and not watch the conductor, and just listen to Drewes. And we would be in synch. I don’t think I ever told him that.”

“He knows how I play, and I know how he plays, and together we make one good trumpet player,” Gardner kids.

Big Bird and the Angels

In conversation Drewes is less interested in talking about his talent than in telling stories—a gift all of his friends mention. On a recent Friday when Drewes was off from Birdland, Lee says his fellow trumpeters kidded that “he’s probably at some function with a whole bunch of big name stars and rich people, and somehow he’s in a corner with five celebrities and he’s the one telling stories.”

And he has so many, and they’re all so entertaining, it’s hard not to want to mention all of them. There’s the time he was tossing a football around on the street between shows on a closed off block of 45th Street, and a passerby stopped to ask where he’d played college ball. It was Don Shula.

Or there was the time that, while working with the Sesame Street band, which he did for many years— “It was fabulous, we were in a studio up on 57th Street, 7 guys, and every day was different”—they were got asked to cover “Fly Me to the Moon.” “They had this little character, Slimy the worm,” Drewes explains. “So of course what song were they going to do? ‘Slimey to the Moon’.” The show had the perfect guest for the number: Tony Bennett.

Usually the music director would sing dummy vocals to go with the band’s performance for the performer to listen to. But for this number the engineer insisted that Drewes—who has more than a passing resemblance to Bennett—do the vocals. And his impersonation of Bennett was so spot on, when Bennett heard the track he said, “Who is this guy? He’s pretty good!”

For a time every Sunday at midnight Drewes and a “weird mix” of people—“there was a guy who wrote for Hockey Magazine, there were cops, stage hands, a bunch of musicians”— would play hockey at an indoor rink on the 23rd floor of a building in Midtown. One night, “This guy comes around and throws me a beautiful pass. I whack it right through the goalie’s leg and score a goal.”

They went back to the bench and the other guy took his helmet off. It was Bob Dylan.

Just as Lee talks about Drewes, Walsh, and Agraz as friends who have looked out for him, Drewes has his own list of angels, “guys that are not with us any more, but they look over my shoulder.” One in particular stands out: Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison, a trumpet player known for his work on the muted trumpet, especially for Frank Sinatra. “Just before From Here to Eternity, Sinatra was kind of down and out,” Glenn explains. “He wasn’t as popular as he was. And he decided to do this album, and he told the musicians, ‘If everything goes well, you’ll be with me for the rest of my life.’ And Sweets was the trumpet player.”

The two of them met on a 12-week international tour. “For the first week or so I was afraid to talk to him,” Drewes admits. “But it turns out he was one of the most beautiful people.”

Years later, Drewes was on his way to work when his wife said they have to talk. “I don’t know if I can do this,” she told him. “I’ve been to a priest, I’ve been to a psychiatrist. I went from being a single woman to married with three kids and having a house in like 2 ½ years, and I’m just freaked out.”

“I don’t know if I’m going to be here when you get back,” she said.

But when he got home that night, she was there in the kitchen cooking and humming a tune. “I actually went out to look at the number on the house to make sure I had the right place,” he says, laughing at first. Then suddenly there are tears in his eyes. “I almost start crying every time I tell this.”

“So I walked in,” he tells me, “and I said, ‘Babe, how’s everything?’”

“She goes, ‘Everything’s great. Forget what I said this morning. Everything’s great.’”

What changed, he wondered. “Sweets called.”

At this point it had been years since Drewes had seen Sweets. “Did he want to talk to me?” he asked. “No,” she said. “He just wanted to talk to me.”

Drewes has no idea to this day what Sweets said. But it helped his wife tremendously. “I don’t know what I was thinking,” she told him. “Forget it. That’s done. Everything’s cool.”

“And that’s why he’s my angel.”

Harry “Sweets” Edison, taken by Rick Edison, 1988.

All That Jazz

A shot of the Chicago orchestra from some years ago: Drewes is last row, center, Gardner to his left. Bonvissuto is just in front of them.

The current revival of Chicago has been on Broadway for 28 years, and Drewes has been with it for 16 of them. “It’s beautiful. People who come from out of town can get it, and everybody wants to see it.” He clearly loves being in the band. “It’s like Phantom of the Opera, except everybody here likes each other,” he says, chuckling.

I wondered whether that interaction he has with the actors at the top of Act 2 was in the script. Says Bonvissuto, who has been with the show its entire run on Broadway, “It was suggested that there should be that kind of energy and relationship. But it’s very authentic, too. The cast really appreciates us, and we appreciate them. It’s one of the things that makes the show fun to do, even after all these years.”

Drewes can’t remember exactly how his back and forth he shares with the cast during the entr’acte started. “It happened once, and then it happens every time after that.” And while the heart of that moment is him bringing the heat, followed by Bonvissuto on the trombone, Drewes directs his praise to the actors. “Mike Scirrotto, he’s great. He’s one of the guys over there, busting my chops.”

I wonder what keeps the show interesting to do 8 shows a week for so many years. “What keeps it interesting is trying to play it without messing it up. My goal is to play a perfect show. And that keeps it interesting for me because it’s never happened,” Gardner says, laughing. “And Drewes is the same way. We’ll go, this is going to be the show, we’re going to play it perfectly. And inevitably by the third or fourth tune one of us has messed up and we’ll go okay, we’ll try tomorrow.”

Drewes agrees. “You try never to mail it in. There are days sometimes, you can’t help but not be a 10, but you try to be a 9 and a half. You have a job to do. You don’t want to be there screwing it up. And you’re playing with musicians—you don’t want to get here and suck.”

But for Drewes it seems like ultimately it always goes back to the audience. “They asked Joe DiMaggio,” he tells me, “‘Why do you play it at 10 all the time?’ And he said, ‘Because a lot of people in that crowd have never seen me play before.’”

When you’re talking to Glenn Drewes, his delight in the work is always married to a deep desire to make people feel happy.

And underneath it all there seems to be in him a constant sense of wonder. “I’ve just been so blessed to sit beside and play with guys that I used to listen to and dream about as a kid,” he tells me. “I’m just the luckiest guy in the world. I really am. It’s not that I’m the best or anything. I’m pretty good what I do, but I’ve just been at the right place, at the right time.”

I’m sure that’s true, to some extent. But after getting to meet Glenn Drewes and talk to others about this talented journeyman who embodies so much of what it is to be a musician in New York City, I think we’re pretty lucky, too.

Thanks again to the International Trumpet Guild and Peter Wood for allowing me to publish this here. And to Glenn Drewes, who answered a card covered in my chicken scratch to do this interview, and then waited so patiently as I put it together.

If you’re interested in learning more about Glenn, you can find some great interviews on YouTube. I love this one he did a couple years ago with a couple other trumpet players. It’s a great conversation about playing the trumpet.

I was hooked on this article when I read, "...as he sipped a bit of the brown stuff." What a wonderful descriptive line, that put a smile on my face as soon as I read it. :-)

I think this might be my favorite article of yours, which is saying a lot. Thanks for sharing Mr. Drewes with us. Makes me want to go see Chicago again. I don't know if I saw him at the Big Band show I went to, but I remember you speaking of him. Kudos on this one!!